Design for desirability

Recently, I’ve come across fragments of the writing of Kenya Hara. I’ve been trying to track down the primary sources for further investigation, but the key source, his book, Designing Design

In the meantime, here are the second-hand fragments I’ve found so far, which, pieced together, begin to tell an interesting story about desire and product design.

In a paper entitled Meaning and Narration in Product Design (PDF), presented at the Designing Pleasurable Products and Interfaces Conference in 2009, Dagmar Steffen references Hara’s work for Muji:

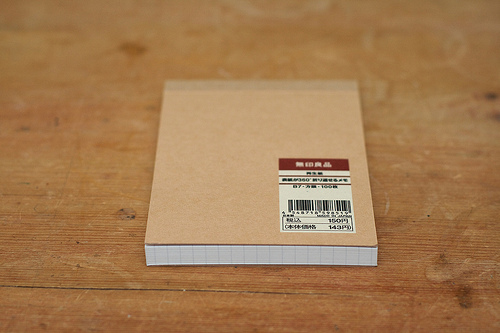

Designer Kenya Hara reports on the strategy of the Japanese retailer Muji: “As a brand, Muji has neither striking idiosyncrasies nor specific aesthetics. We don’t want to be the thing that kindles or incites intense appetite, causing outbursts like, ‘This is what I really want’ or ‘I simply must have this’. If most brands are after that, Muji should be after its opposite. We want to give customers the kind of satisfaction that comes out as ‘This will do,’ not ‘This is what I want’. It’s not appetite, but acceptance.” And he justifies this attitude: “I wonder if humankind, having rushed after desire, has finally reached an impasse.”

The theory of fabricated desire is one of the pillars of early anti-capitalist thought. But while many anti-capitialists may still feel this way, in the development of a more nuanced, sophisticated, sustainability-focused approach, desire has come to be seen as something we must work with. Sustainable products should be as desirable as (or more desirable than) their unsustainable alternatives.

But given the uphill struggle we face embedding sustainable thinking in design and consumption, we must question all our assumptions. By catering to — or even fanning the flames of — desire, are we tacitly accepting the rules of an unsustainable game? And by playing that game, are we setting ourselves up for defeat against opponents stronger than ourselves?

If we accept that the anti-capitalists have unrealistic — undesirable — ideals, what are the alternatives? What could a post-desire design culture look like?

Muji is certainly an interesting take on this idea. Here’s David Aaker’s take:

Muji can be described as a reaction to the glitz of Tokyo’s Ginza shopping district and other shopping centers that are filledwith brand after brand, each trying to be more upscale than the last. In Japan, Muji is anti-glitz. The badge of Louis Vuitton is the polar opposite of Muji. Ironically, this desire to eliminate self-expressive benefits actually provides self-expressive benefits. Shopping at Muji and using Muji products make a forceful statement about who you are. You are above looking for badge brands. You are, rather, a rational person interested in the right values, and you choose to connect with a firm that is interested in promoting social good and satisfaction from life.

[…]

Muji is a most unusual brand story— a non-brand that delivers emotional and self-expressive benefits. Today’s trends make the story become even more interesting. Consumers have seen the downside of the debt-driven commercialism excesses of today’s society. There is almost a craving for the simple, away from the prideful and self-absorbed brand benefits and toward more satisfying values. A desire for fewer additives in food, for entertainment systems that are easy to operate, for less product confusion, for sustainable consumption and on and on, is becoming visible. It may be that the simple and unassuming may become more of a mainstream formula rather than a niche strategy. If so, Muji may become a brand role model that others look toward.

As it happens, I’ve quoted two sections that for me, don’t quite hit the mark. Muji as a hyper-rational identity brand, or Muji as purveyors of relaxing simplicity: these characterisations only partially reflect the truth about their design philosophy. I believe there are more interesting facets — which may be difficult for Western minds (certainly my mind) to grasp. An adjacent passage from Hara’s book is quoted by Paul Kim:

Both the consumer society and individual cultures, chasing after desire and driven by appetite, are hitting a wall. In this sense, today we should value the qualities at work in acceptance: moderation, concession, and detached reason. Might acceptance be a form with one more level of freedom? Acceptance might involve resignation and slight dissatisfaction, but raising the level of acceptance thoroughly eliminates both. To generate “this will do,” by creating this very dimension of acceptance, one that is clearly self-confident and also truly competitive in a free economic society: this is MUJI’s vision.

In his analysis of acceptance, there’s ‘reason’ again (and hey, I’m all for a more application of reason), but also ‘moderation’ and ‘concession’. In a review of the book, Andy Polaine unpicks it some more:

This philosophy of balance plays a part in his views on sustainability, obviously, but is also deeply embedded in the MUJI brand, for whom Hara is the Art Director. There is a large section on MUJI and the no-brand philosophy behind it, part of which is about not designing for desire. It is not that objects should not be well-designed or aesthetically pleasing, but that this isn’t the end point. Hara’s aim with MUJI to design for adequacy.

On the surface this sounds, to Western ears, as striving for mediocrity. (I imagine this sounds particularly so to North Americans – correct me if I’m wrong). The nearest Western brand with a similar philosophy is maybe IKEA, but not quite. Hidden in this philosophy of adequacy is an expression of balance, of consuming only was is required, not more not less, of not designing newer versions for the sake of technological advancement. It’s not about the next big thing, it’s about the next small thing.

These are just fragments, and the real meaning of Hara’s philosophy is, for me, still just beyond reach. But if we’re willing to question the need to design for desirability, these dim lights may well be a useful guide.