Lessons from Maker culture

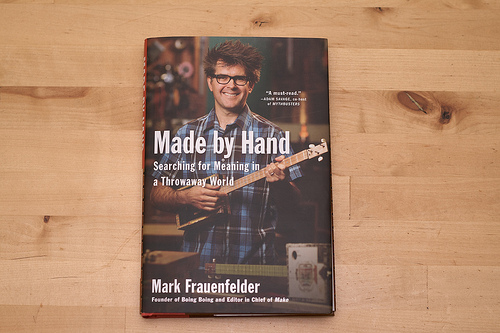

My sister gave me a copy of Mark Frauenfelder’s Made by Hand

For me, this is partly born out of a desire to engage in physical creative projects as well as digital ones. I spend enough time in front of a screen as it is. But I’m also interested in the wider social implications of a rise in maker culture. Craft activity can teach us lessons that apply beyond the realms of physical objects and their production. And these lessons form an undercurrent throughout Frauenfelder’s book.

The thrill of production

In a society in which we pay other people to produce almost all the things we use, it is a novel thrill to make something for yourself. Industrial mass production has taken responsibility for fulfilling so many of our needs that we rarely experience the pleasure of making something for ourselves.

Some products are better for being made by someone else on our behalf, but we have ceded control over production in so many areas, that we often forget that we once did it ourselves. Food is a prime example, from family meals to food-on-the-move; foraging for wild food to growing our own fuit and veg. All aspects of our lives that we have ceded control over in the recent past. Home-made bread may now be the preserve of the yummy-mummy brigade, but there is no reason why it should be so. Frauenfelder takes on a more exotic challenge. He talks about his project to produce (‘grow’?) his own home-brewed micro-biotic foods, such as kombucha, a kind of mushroom tea.

Kombucha colony close up by Debra Solomon (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs Licence)

Kombucha colony close up by Debra Solomon (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs Licence)

He quotes Sandor Ellix Katz on the ownership of food:

There is a mystique around fermented foods that many people find intimidating. Since the uniformity of factory fermentation products depends upon thorough chemical sterilization, exacting temperature controls, and controlled cultures, it is widely assumed that fermentation processes require these things.. The beer- and wine-making literature tends to reinforce this misconception.

My advice is to reject the cult of expertise. Do not be afraid. Do not allow yourself to be intimidated. Remember that all fermentation processes predate the technology that has made it possible for them to be made more complicated. Fermentation does not require specialized equipment. Not even a thermometer is necessary (though it can help). Fermentation is easy and exciting. Anyone can do it. Microorganisms are flexible and adaptable. Certainly there is considerable nuance to be learned about any of the fermentation processes, and if you stick with them, they will teach you. But the basic processes are simple and straightforward. You can do it yourself.

Industrial production (and the seductive sheen of brand advertising that supports it) encourages us to believe that branded products are in a different category to those we might attempt to make ourselves. That there is some ‘special sauce’ that the brand can add which we don’t have access to. While this may be true in some industries (semi-conductor manufacturing, for example) it is not the case in many of those closest to our hearts.

Conformity

Not only are we dissuaded from making our own stuff, but model of industrial production and branding moulds our behaviour towards the products we buy, and the way we use them. Frauenfelder writes about another of his projects; to make a cigar-box guitar.

cbg1 by steve lodefink (Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic Licence)

cbg1 by steve lodefink (Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic Licence)

He talks to one of the ‘alpha-makers’ in the field, David Williams, otherwise known as One-String Willie:

On his website, Williams mentions Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay “Self-Reliance.” Williams explained that Emerson believed “society tends to push people towards conformity, and while conformity is OK in many areas of life, like following traffics laws, or wiring your house correctly, it is less welcome in other areas, such as the arts. A homemade instrument allows — forces — you to break out of the rut of artistic conformity, as there is no established way of playing, there is no established way the instrument is expected to sound, and there are no books to tell you how to proceed. You need to teach yourself how to make music come out of your homemade instrument, drawing from your experiences with other instruments and from the music that is inside your head. If you view this as a journey and not a destination, it is a liberating and joyful experience.”

When we make the things we need ourselves, not only do we regain the power of production, we also enjoy defining our own usage of those things.

Infantalisation

Consumerism at its worst, infantilises us. It promises to attend to our needs in exchange for cash. In Co-opportunity

Human babies are psychologically and physically dependent. So much so that, in the early stages, infant observation studies point to a kind of merged observation with their mother. ‘Omnipotent’ was one of British psychologist Donald Winnicott’s words for the experience of this stage (the full phrase is ‘subjective omnipotence’; the baby isn’t actually a god, she just thinks she is!). Winnicott used this term to describe the state of being prior to weaning – a stage when fantasies are the reality, in that your experience is of a world (principally your mother) that seems to exist for meeting your needs. Hence it’s also a stage of magical thinking. When the baby cries a breast appears. Which Winnicott argued would be experienced by the baby as if it had made the breast appear by magic.

The underlying promise of consumerism is similarly that you will never go without, that your dreams will come true; it’s the fantasy of cornucopia.

Industrial mass production explicitly promises us regularity, conformity and safety. Implicitly, often through the mechanisms of consumer advertising, it offers us an infantile omnipotence. Explicitly, it offers to do this in exchange for cash. Implicitly, it also costs us power, ownership, creativity and personal growth and expression. Sometimes also taste, quality — and yes, safety too.

Taking responsibility

Why is this important? Because active, adult engagement — taking responsibility — is necessary in order to solve problems. On the personal scale (quitting smoking, saving for a rainy day, fixing a dripping tap), but also on the social scale. Active citizenship is vital in solving big social problems.

An infantile culture will never, for example, tackle climate change. An infant who sees a sibling do something wrong and get away with it will copy that behaviour. An adult (on a good day) will do the right thing, regardless of what others are doing around him. The research on environmental behaviours shows that people look to others to gauge the social norm for any behaviour, from littering to taking short haul flights. We are constantly testing the strength of the social contract that binds individuals, communities, business and government together.

Those who believe we can all be ‘nudged’ into better behaviour place great stock in this phenomenon. While it is is certainly real, it is amplified when individual players are not willing to make a stand, to take personal responsibility. Putting smiley faces on recycling bins, or producing reusable shopping bags that proclaim their green credentials for others to see — these kind of approaches are not going to result in the step change in human society and behaviour that needed to fix the big problems we face today. We need a large-scale awakening of personal responsibility.

And I use the word ‘awakening’ deliberately: this needn’t be a chore. Taking responsibility — doing it ourselves — as Frauenfelder shows, can be thrilling and creatively fulfilling. The transition from an infantile phase to an adult one can be painful — just ask any teenager — but the rewards are huge. DIY, craft and maker culture are all ways we can do this in the context of physical objects, arts, design and in our homes. I’d like to see us extend these approaches out to all aspects of our lives. In sustainability, for example, not only should we be looking to normalise green behaviours, but we should be showing that such behaviours are empowering. That choosing to be green is a thrill.