How many uses are there for a shoe?

I’ve been spending some time over the new year reflecting on my work, and trying to develop ideas about how I package what I do (which is rather nebulous and difficult to describe).

That calls for divergent thinking, amongst other techniques (e.g. needs analysis, prototyping and validation). So I read this blog post, Divergent thinking in children, by James Allen, with some interest.

In it, he talks about the apparently natural skill that we all have as children to generate lots of ideas (or solutions to a problem), and how this seems to be lost as we get older (and possibly as we go through the education system, which values convergent thinking).

He references an experiment designed to test our divergent thinking abilities (via an article by Len Brzozowski, How many uses are there for a shoe?). Quoting from the Brzozowski article:

Creativity researchers George Land and Beth Jarman recently used questions like “how many uses are there for a shoe?” to create a sort of IQ test for creative thinking. In one interesting study, they administered their test to groups of 5, 10 and 15 year olds. The results are described in their book “Break Point and Beyond: Mastering the Future Today”.

An impressive 98% of 5-year-olds scored at the “genius” level in such a test of divergent thinking. Test-takers age 10 however, saw their number drop to 32%, and only 10% of high-school-age test-takers scored at the “genius” level.

I was interested in the exercise, not so much as a test, but as a possible method for practicing divergent thinking, or as a warmup prior to tackling a real problem. Would practicing this kind of thinking make you better at it? Could you get your brain into a divergent mode by generating lots of ideas about an unrelated subject? Would this warmup put you in a good place to tackle a real problem?

So I had a go.

What I did

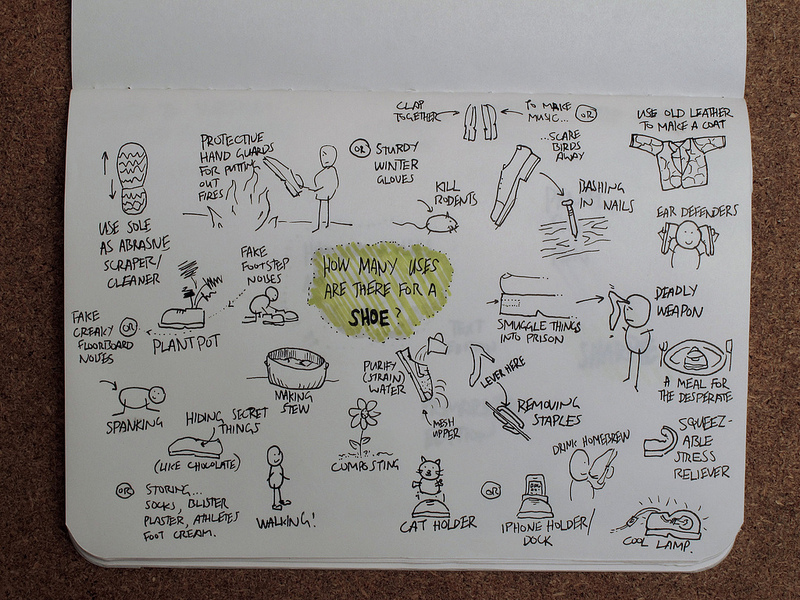

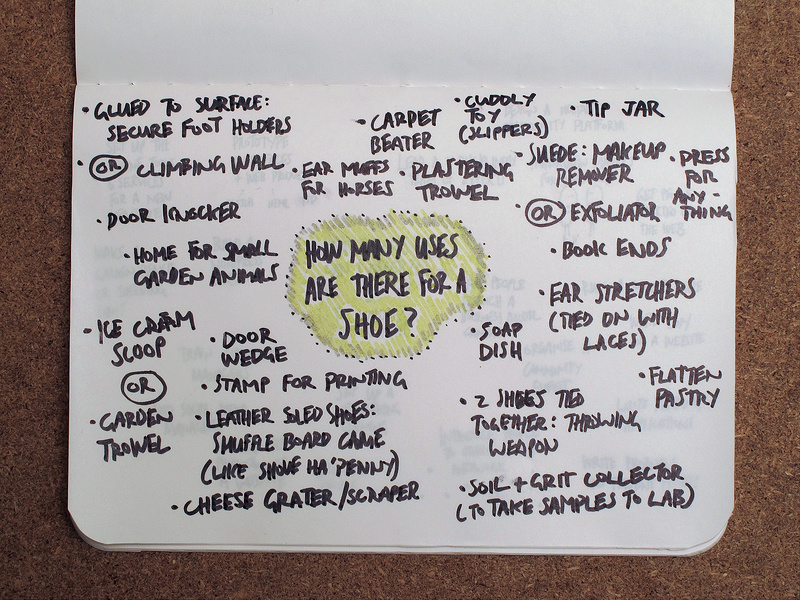

I spent about an hour trying to jot down as many uses as I could think of for a shoe. I had, at the back of my mind, a target of around 50 (which is pretty much what I managed), but I tried not to focus too much on the number, as I didn’t want the pressure of a target. Instead, I set myself the softer target of filling two pages in my sketchbook.

I tried filling the first page with visual sketches of the ideas, and the second page, just writing them down as descriptions.

I’d skimmed the articles linked above, but intentionally didn’t read too much of the theory, so I could approach the exercise with only my own pre-conceptions.

What I came up with

It’s not really the point, but if you’re curious, here’s what I scribbled down on my two pages.

How I felt

Anxious

Initially, I was very conscious that it didn’t feel like work. Was I being productive? Was I Getting Things Done™?

Even worse, it didn’t look like work, and I didn’t want to be caught playing. I was worrying about what others might think. While this might be a personal hangup, there are many business contexts where openly playing, or even doing work that looks like play, may be frowned upon.

I deliberately tried not to pressurise myself with a target, but I’d noticed this line about ‘98% of 5-year-olds scored at the genius level’, so I felt some pressure to achieve a good ‘score’. It was is if there was some imaginary ‘I am creative’ checkbox that could be ticked off when I’d got to some certain number of ideas. (The softer target of filling 2 pages did help to ease this off.)

Rationally it doesn’t make sense – I wasn’t trying to test myself – but it’s important to consider these kinds of anxieties and mitigate against them, especially if you’re trying to help other people through a process like this. Who wants to fail the ‘are you creative’ test? It’s like scoring low on an IQ test, or your child coming back from school with a D for their homework.

Having fun

While using just words was quicker, it was way more fun to sketch them. And in most cases, easier to communicate the idea.

I’d be interested to find out if the whole exercise becomes easier – and more fun – with practice.

After I’d put down the first few obvious ideas, I quickly started down more outlandish avenues (cat holder, anyone?). While these weren’t necessarily useful idea in themselves, they opened up areas for exploration that I’d otherwise have missed.

The humour and playfulness of silly or surreal ideas makes the whole exercise enjoyable and of course, creative. A good thing, and doubly so, because you’d likely be using an exercise like this to help you get out of a rut; you’ve already identified that you need to explore some hitherto unknown territory.

Analytical

Most interestingly I found the exercise a great way of analysing the problem space. Maybe that’s a counter-intuitive outcome, analysis and creativity often being characterised in opposition.

As I imagined more uses, I started to identify some common qualities inherent in the shoe that these uses flowed from. For example, I had the idea of making compost out of old leather shoes, or stitching together old uppers to make a coat. This led me back to the material characteristics of shoes (being made of leather) and opened up new ideas that made use of the same characteristic (e.g. making a stew).

It also identified axes along which I could travel (or parameters I could tweak) to generate new ideas. If these ideas are all derived from leather shoes, what happens if you change the material to woven nylon, as in a pair of trainers. Then you could use a shoe as a kind of liquid strainer.

Here are some characteristics I worked back to:

- Functions (protection, adjustability, removability)

- Features (shoelaces, hard heels)

- Materials (leather, nylon, rubber)

- Material sources (man-made, natural, animal-derived)

- Material properties (smell, taste and feel)

- Styles (high heels or trainers)

- Lifecycle (new, or waste)

- Dynamic properties (weight, flex, aerodynamics)

I can see how this would be really useful in coming up with messaging ideas or in brand work, where you’re looking for compelling, essential concepts. They’re not easy to dream up. But the rules of this game (think of lots of ideas) force you to consider what properties your existing ideas are coming from, and how you might tweak these to generate new ideas. That gives you a much better understanding of those essential properties.

Aha moments

Related to the above, it’s worth noting that the ideas didn’t flow in a smooth curve. There were sudden jumps in my productivity when I discovered a new axis to travel down, and immediately 3 or 4 more ideas became obvious. That’s an ‘Aha moment’, and it’s worth noting because it’s these kinds of moments that make creative work rewarding. If your working practice sets up good conditions for having Aha moments, you’re well placed to have good ideas.

Turning to a real problem

Then I had a cup of tea.

And after that, I tried applying this technique to a real problem I was trying to solve. This proved much more difficult.

Probably no surprise. One of the characteristics of real problems is that they’re often hard to solve.

Shoes are very open. They reveal themselves easily. They can be interrogated visually and physically; you don’t need to interview them to find out how they work. In contrast, the problems I was working on were focused on my own work. I had to look inside myself, and that’s always more difficult. Even if I was working on someone else’s problem I would still have to interrogate them in some way (e.g. through interviews, shadowing, walk-throughs, etc.).

I also realised that the creative qualities of the exercise flowed from the type of question I had asked. The subject was physical and tangible. The small number of sensible uses quickly invited a – literally – fantastic response, which in turn opened up many areas for exploration.

So as well as helping me understand the nature of divergent thinking, this exercise helped me look at other ways of asking questions. One area to consider next is what makes a question interesting, and how can intractable problems be reframed into fruitful stimuli for divergent thinking.