A conversation with Natalia Buckley

Photo by Roberta Mataityte

Natalia Buckley is a hacker, designer, and creative technologist. She’s originally from Poland and now lives in Brighton on England’s south coast, a city famed for its appetite for experimentation.

I met her at Lighthouse, Brighton’s “digital culture agency” to talk about her recent projects and why she makes the things she makes.

This interview was originally published on Makezine.com

This extended version includes a tangent that didn’t make that cut: When the interview was over, we left the recorder running, and chatted about something that I’ve been turning over in my mind recently – how can making stuff help people solve problems, or think creatively?

Natalia had an interesting perspective on this, so I transcribed the conversation, and I’m publishing it here, for reference. It’s still half-formed – a hunch more than a statement – but I want to put it out there so it can combine with other hunches.

Natalia studied design at Goldsmiths College in London where she was able to experiment with design practices from clay to CAD/CAM. Natalia was exposed to a broad range a fabrication techniques and design disciplines and also developed an awareness of design as a kind of research.

“If you ask people what they think, they don’t necessarily tell you the truth–or they’re not necessarily aware of the truth,” she says. “They’ll tell you one thing but sometimes they do another. But when you make an object, then you put it in a real life situation and let people use it, not only do you learn about the object itself, but you also learn a lot about people: how they interact with one another, how they interact with the object itself. You can ask probing questions about people’s beliefs, even beliefs that they don’t know they have.”

She’s recently completed a residency as part of the Happenstance project, a program of residencies by technologists at arts organizations across the UK. Along with James Bridle, Natalia was a resident here at Lighthouse, working in the building alongside the arts administrators and curators immersed in the ebb and flow of life at a busy cultural organization.

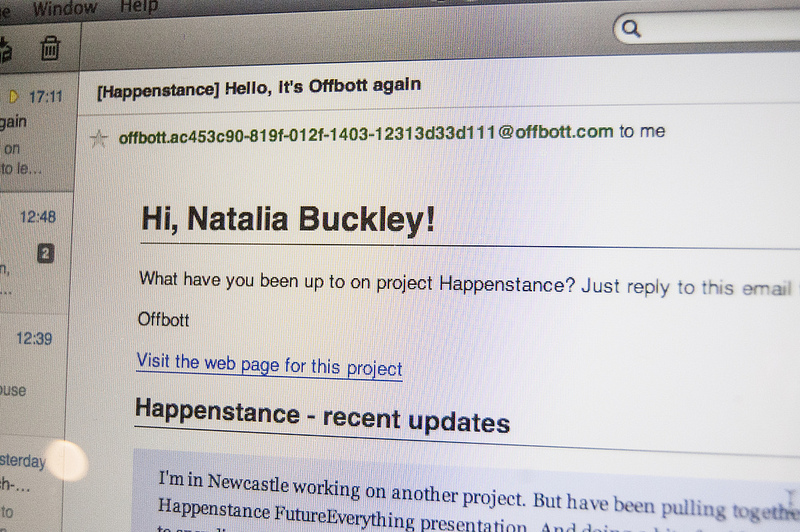

One of the projects Natalia and James were working on was called Offbot (as in office-robot), a “mostly friendly” tool for collecting people’s thoughts, insights, and activity as they’re working on a project.

Photo by Natalia Buckley

While there are plenty of tools available for project management and team communication (the likes of Yammer and Basecamp), Offbot is aiming at something different.

“Offbot is a tool for teams to keep a journal together,” she says. “Offbot contacts you once a day and asks you what you’ve been up to. It’s not a task management tool. It’s more a tool to reflect on your own work, and how your team works together. And because it contacts you out of the blue – it emails you at random times of the day – most of the time, people reply with the first thing that comes into their minds.”

There is a very carefully designed interaction between Offbot and its human colleagues. Offbot asks them what they’re up to in a friendly way. They don’t have to respond and it’s not their boss. All added together, these small, personal interactions result in an archive of project activity that’s very different to a more traditional project review.

It collects thoughts in the moment. “You get the kinds of replies that are more meaningful or harder to recall when you’re talking about a project after it has happened; those fleeting moments of activity that are really interesting” says Natalia.

Offbot was originally designed to give teams a way to look back on projects, but as early prototypes were rolled out in the Lighthouse office, new uses emerged.

“People would send in their daily note, but then realize ‘Hey, this is an interesting idea, I might write a blog post about it’, or people who’d been away would come back an catch up on what the team had been doing while they were gone.”

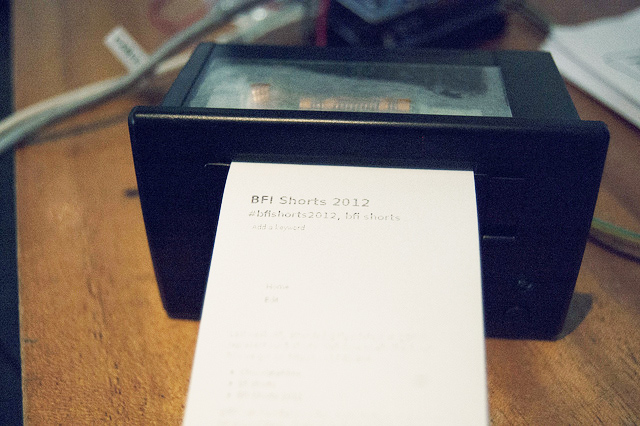

Another project Natalia hacked on while at Lighthouse was called Audience.

Photo by Natalia Buckley

Arts organizations collect huge amounts of feedback from their audiences, through feedback forms, online surveys, at opening events, and in comments books. But all these methods have limitations. They invite responses, which tends to sway people to either flatter or criticize and respondants are a self-selecting group.

Feedback also tends to be typed up and filed away ready for use in the next funding bid or project write-up. The tools do little to connect the people who put on the shows with the people who visit.

Audience goes direct to the source, scouring social networks for mentions of shows and artists exhibiting at Lighthouse. It collects and archives the spontaneous comments, shared between friends, that have an honesty you won’t find in a comments book. But Audience is more than social media monitoring software. It’s based around an internet-connected thermal receipt printer which prints the comments out in the office for the production team to see first hand.

“It’s really exciting,” she says. “Suddenly someone else’s thoughts about your work arrive in the office – you feel really connected to it. “

A lot of work in an arts organization is administration. The people behind the scenes are not close to the audience. This project provided a way of connecting the people in the organisation back to the audience.

“Suddenly your work matters to real people. I think that’s really sweet.” she says.

Both Offbot and Audience are quite simple projects, at least physically. Their impact lies more in their behavior, and how humans interact with them. There’s a subtlety of interface that’s maybe not surprising to see when you consider Natalia’s design background.

“People would talk to Offbot as if it were a person ‘Hi, heya, how are you?’ or sometimes, ‘I haven’t emailed you for a while, I’m really sorry, I’m going to try and do it more often.’ When there was a bug and Offbot was sending multiple emails one day, people were like ‘Hey Offbot, why are you so needy?!’”

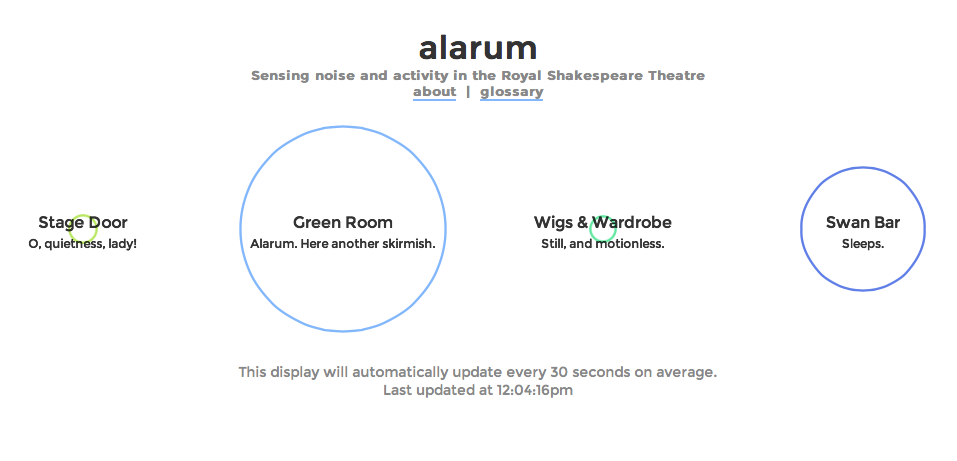

Since the Happenstance residency finished, Natalia has been working with Caper on a project for the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford, called Alarum, a term used in Shakespeare’s plays to indicate a sudden noise, alarm, or call to arms. Alarum is an exploration of the theatre building itself.

“The building has a life of its own, but you don’t actually get to see it. Wouldn’t it be interesting to see how much goes on there? And there are so many areas that are out of bounds to you and me, all the backstage areas, the offices, the green room; all these areas where so much happens, and you see not a little bit of it apart from the resulting performance.”

Natalia placed infra-red sound and motion sensors in four spots around the theater in the places where activity happens, but not the main activity – the performance. The sensors collect data and, using network-connected Arduinos, feed that data to Cosm, a platform for sharing data from the ‘internet of things.’

Photos by Natalia Buckley

“They’re really crude devices, and the sensitivity wasn’t great, but it didn’t really matter because in this case, what we’re trying to look at is the grand overview of things, rather than the exact level of noise or movement.”

Then she built a data visualization app (online here) that interprets the data to show what is happening right now in those four places. It doesn’t show the literal sensor data, but instead tries to give a sense of what kind of activity is taking place, for example a sudden burst of energy, stillness, or a continuous hum of activity.

It even uses Shakespeare’s stage directions to help you understand what is happening. When I looked at the Stage Door display, it was tagged with the direction, “O, quietness, lady!”

“The longer I look at the data, the more I see possible improvements that could be made, either to visualization, or to help people to understand the data,” says Natalia.

This is a common thread throughout her work. These objects aren’t finished products, they ask as many questions as they provide answers. They’re ideas that Natalia seeds out in the world to observe and gather data on what they find. Then this insight can be folded into the next project, and the cycle continues.

“I’m just making speculative things, that don’t necessarily fully exist in the real world, but help us learn something,” she says. “I’m a social observer. The sole reason I make things is to learn something about other people. Because I find other people fascinating. My work in technology is basically about people. People constantly interact with technology and I can make technology to watch them do stuff!”

You can find out more about Natalia on her website or blog. Or follow her on Twitter.

Andrew Sleigh lives and works in Brighton, and is a co-founder of Brighton Mini Maker Faire. His favourite tool in the workshop is the sewing machine. You can follow him on Twitter, too.

AS: I’ve got a puzzle … so I’m asking the smart people I know about this. I think there is something valuable about physically playing with stuff as way of engaging and thinking about problems…

NB [jumps in]: OK, so this is something I’ve been thinking about a lot … so Instagram changed their terms and conditions and I was really feeling like that was not a good thing for me to be on Instagram, and I couldn’t put my finger on it. I started to not understand what it was about it that made me feel uneasy. Is it the fact that they’re opening up more, or is it the fact that the the terms allow them to advertise stuff to me, or is it use me for advertising. I wasn’t sure what it was that I suddenly disliked about it.

So in order to think about it, I made my own tiny little Instagram, where I just put stuff in Dropbox, and it automatically publishes stuff to a little website. … In order to think about what it is I want to say about it, or what it is that I have a problem with, I have to actually make something.

This is something – again, back to my student days – this is a valid form of thinking. When you’re drawing you’re thinking, when you’re making stuff, you’re thinking, and that’s OK. You don’t have to think by just looking at the wall, or a screen.

So sometimes, to bring out what it is you’re trying to say, or ask, there’s no better way than to actually make something.

_AS: In that Instagram example, in the course of doing that project, did you reach some conclusion?

_

NB: Yes, and I’ve been thinking about that a lot. And I think it’s the trade-off between what I thought it was, when I first signed up, and what I understood the product actually was – these things were at odds. And I liked my own vision of what it should have been, and the one that was actually true, I felt very uneasy about.

_AS: So did you find that the thing you’d made yourself was your ideal vision of the product?

_

NB: Absolutely not, it was rubbish! First of all, it’s missing the most important thing: my friends – there are no other people on it. Also, I thought my problem was with sharing, so I made something so I could probe my sharing habit, or what I’m prepared to share, or how i’m sharing things, but it wasn’t necessarily about that. It turns out that it was more about what I’m sharing, with which people, and how much control I have over it. That was the interesting thing, and not my sharing.

The thing was a failure, but it was a useful failure to make.

_AS: So you were sitting there coding away, engaged in the space of the problem, but not actually sitting there thinking about Instagram, or reading the terms…

_

NB: Exactly. I was making decisions, and making trade-offs, and thinking about how I was going to make it. And through that, it gives you space to think about deeper things, without having to engage them head-on.

AS: Is the benefit then, that you’re not looking at the problem directly? That you’re playing with it, but you’re not blinded by it …

NB: Yes, you’re engaged with something that keeps it on your mind, but you’re not directly thinking about it. And also the resulting thing is a research object that you can use and play with, and learn something from.

_AS: Do you think that you could teach that to someone else? Specifically to someone who’s not a designer or programmer?

_

NB: Yes, I think so, because I think it’s something that people just do. Why is it that people like knitting? It’s because it occupies your hands and your eyes. It’s almost a meditative thing. You think about other things while you’re doing it. …

AS: I would like to figure out a way of sharing this with people who maybe don’t come from that background. Whenever I talk about it to people, they always respond – well like you did [i.e. enthusiastically] – they feel like this is a positive hunch; it feels like there’s something there which has got some value. But what I’ve been struggling with is how do you apply that outside of a product context.

NB: I guess, a lot of hackdays approach things in that way. For example, you’ve got a problem, which could be a big social problem. And you try to ‘solve it’ using technology. So you build something really quickly to test something out. But in the process of building it you are engaging with the problem on a deep level. So you have to ask lots of questions in order to make a thing – you have to make decisions.

And in that process, you either discover stuff, or you ask questions that you hadn’t thought about before. So you’re actually expanding – or defining – the problem space, while making something.

There is often criticism that hackdays don’t result in something that fixes problems, or that this approach doesn’t work with complex problems. And while that may have some truth, people forget that there’s amazing value in having people engage with something on that level.

AS: So do you think that the value comes after the hackday itself?

NB: Yes, the value isn’t necessarily in the thing that you make. The value comes from the fact that you thought about it, and you talked to other people about it. Sometimes that is just a starting point, you carry on thinking about it. And you’ve already asked lots of questions, so you’ve made a really good start.

AS: So if you’re going to make a hackday useful, you need to find ways of getting those people back together again, or re-engaging people. If someone comes to Rewired State, and in the course of hacking on a problem, develops lots of interesting hunches, but then goes away and never comes to another Rewired State, or never gets involved in that kind of social change, then you’ve lost that value – it’s disappeared.

NB: This is a massive challenge for hackday organisers. If the problems you’re working on don’t necessarily have a technological solution, then maybe it would be useful to open up other channels where this thinking could be directed. So say it’s a cancer hackday, so we’re thinking about cancer problems, and we’re trying to solve them with technology, and we actually don’t, but loads of people start thinking about it, and talking to their friends and neighbours about it, and they come up with some ideas, these ideas have nowhere to go…

AS: So that’s a conversation we should continue … over a beer

Some themes which resonate with me here:

- Making stuff forces you to make decisions. That can be a powerful way of crystallising thoughts.

- Making can often be a useful diversion, with the real benefit coming later.

- With collaborative making, this raises an interesting challenge of how you extract that value after the event.

I’m chatting to all the smart people I know about this. So if you have any thoughts on this subject, please let me know.