Alice Taylor: Inventing the Future of Toys

This interview was originally published on Makezine.com

One small tangent that didn’t make the cut, but which I’m personally interested in: We were talking about moving towards a mainstream market, and the scaling up of production that demands. I was curious how that would work with the outfits, which aren’t made by machine. We digressed into a small discussion about the education sytem and secondary markets.

Alice Taylor is CEO of Makielab, a London-based startup that 3D prints customised action dolls called Makies. Customers design their doll on the Makie website, choosing facial features, hairstyles, eye and skin colour, and selecting outfits and accessories. The dolls – fully-poseable, and about 10 inches tall are then printed in London and shipped out. For the Makie and Alice, that’s the beginning of a long adventure.

I spoke to Alice about the adventure that she and Makielab have been on, playing with toys, working with geeks, and bringing 3D printing to the masses.

Alice starts the story in 2010:

“I was at the Toy Fair in New York, and they co-located it with something called Engage Expo. The Engage Expo was ‘digital’ and in the basement, and the Toy Fair was right there, huge and brash, on the main floor, and they weren’t talking to each other at all.

“I had the idea there: I wonder if you can take an avatar and turn it into a doll using 3D printing? Can you take a digital monster and turn it into a toy monster? Or a digital car into a toy car, and so on.

“I knew about 3D printing; I knew there was potential, in the theoretical sense – you can take a digital file and produce a physical object. That idea, ‘bits to atoms,’ had been hanging around. So that’s where it started.”

But Alice didn’t want to make just any kind of doll. She wanted to make a doll that kids could play with creatively. A doll that looked to toys like Lego – rather than Barbie – for inspiration.

“We wanted it to be a doll that you make yourself, and that would encourage creativity. We want kids of both genders to make dolls, and play with dolls – they’re action dolls. We want people to make clothes, and experiment, and play. Because they’re toys!”

Makies looking to the future.

Makies are manufactured using a 3D printing technology called selective laser sintering (SLS), in which a laser fuses together particles of nylon powder to form the individual parts. The process can produce items with very high fidelity and strength, compared with the more common fused deposition modelling process (FDM), often used in desktop 3D printers, where a filament of plastic is extruded to build up a model in layers.

The downside of this process is price, with SLS machines costing an order of magnitude more than their FDM cousins. Nevertheless, SLS technology could be described as just-about-affordable, and Makies are a perfect application for consumer-quality 3D printing. Digitally designed, and each one unique, Makies are a sign today of a much-talked-about future trend in manufacturing: mass-customisation.

“We set out to make consumer-facing goods using 3D printing. The original vision was: virtual goods would produce physical goods; the physical goods you would be able to modify, and that would feed back into the virtual world. That would create a kind of loop between digital and physical. The only way you can do that is with a digital thing that also lives as a physical thing, connected with an identity. The traditional technology for manufacturing toys makes it hard. 3D printing technology makes it possible.”

So 3D printing makes personalised dolls possible. And personalisation is what makes a Makie special.

“You look at a kid playing with an action figure or a doll – they’re story-telling, usually. That’s really creative, and if they’ve had a hand making those characters themselves, that’s even more the case,” says Alice.

The creativity starts at the design stage, before the doll is manufactured. But it continues on after it has been shipped, through play, and further customisation. A Makie is never truly finished, and this is what makes it such a powerful product. It’s a toy that can be made your own, through design, decoration, accessorising and story-telling.

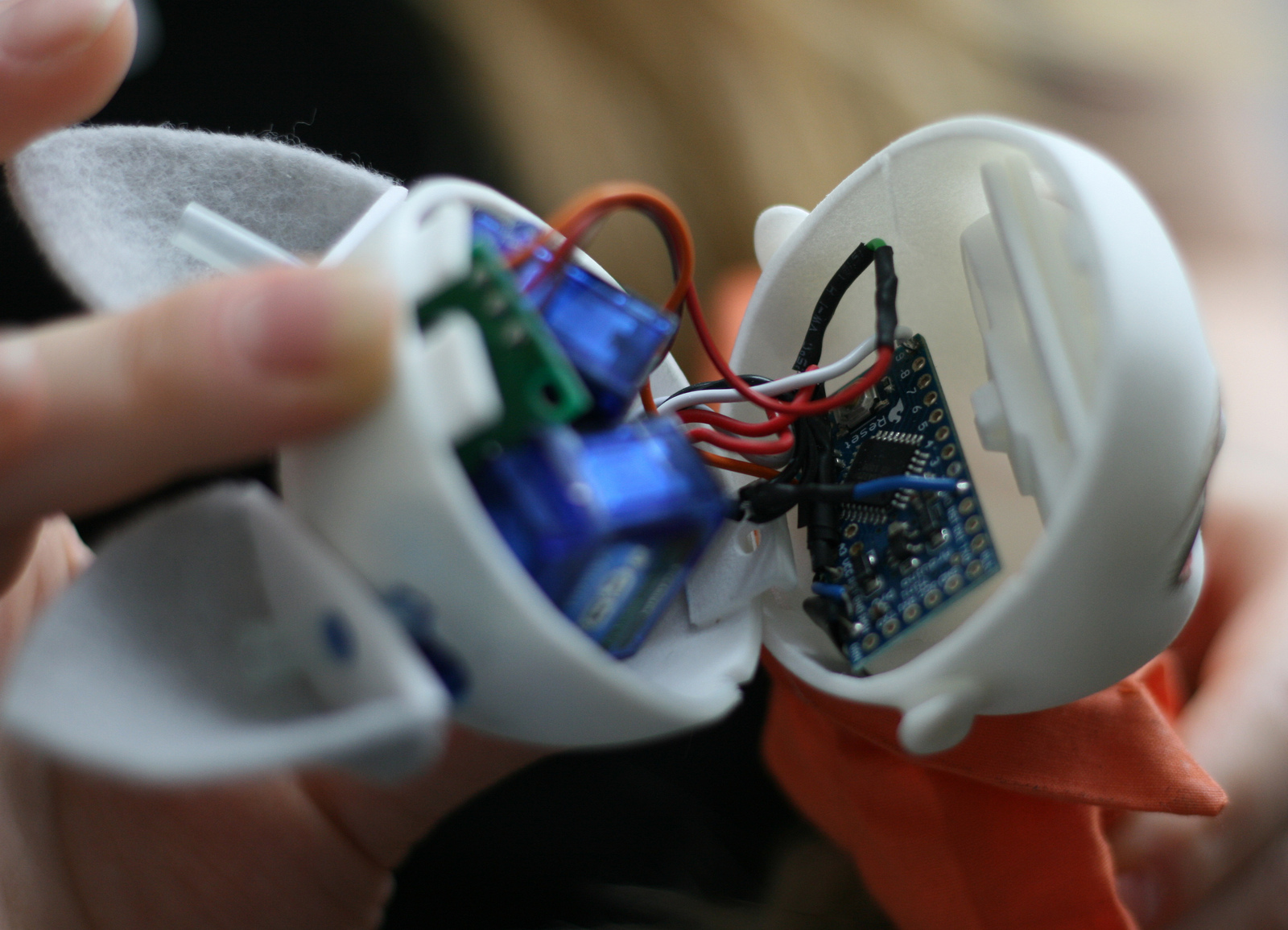

And some customers are going to even greater lengths to personalise their Makie; they’re reaching for the Dremel and the soldering iron.

A hacked Makie that responds to sound. Photo by Sara Long.

Putting toys in the hands of geeks

Tim O’Reilly popularised the idea that what geeks are doing now, the rest of us will be doing in the future. Alice is betting on it.

“If you start with alpha geeks, and learn what they like, inevitably it will become mainstream,” she says.

“Alpha geeks are the canaries in the coal-mine. They’re the ones who will pick something up that most folks maybe wouldn’t understand; they’ll examine it and say, what is this? How does it work? They’ll play with it; iron out the kinks, and in that process the manufacturer or the provider will also learn a lot. And then, when everyone’s ready, it will just bleed into the mainstream.”

Releasing early, developing in the open

Geeks are drawn to unfinished products as platforms they can build on; starting points for experimentation, hacking and misuse. And the natural appeal of Makies to the geek community has been a win for everyone. Geeks get a hackable toy they can make their own, and Makielab get a community of co-developers who can help them test their proposition, and refine the product.

“We raised our first bit of money, and our investors said, ‘your backgrounds are in digital media; how do you know you can do the manufacturing? It’s a big deal; it’s hard work.’ So we spent the first bit of money building the software and manufacturing platform,” says Alice.

“We launched, even though the dolls were only available in bone white – there was no skin coloring. The interface was, well, not the best. And the dolls were £99 [$147] – they have to be, because they cost almost that much to make at the moment, what with us being at the scale we are. And they weren’t toy safety-certified, so we had to target the 14+ age.

“But we said, screw it, we want to put it live anyway, we want to get it out to the alpha geek community; we want to talk to people; we want to see what people want; we want to start figuring out what it is about a customisable doll people love the most.”

It’s been about a year since the first dolls were made available on the website, and in that time, Makielab have built an active community of fans customising and modding their dolls, and sharing the results back with their peers:

“They started putting them in tea, and ink, and sand-papering them – and in the same way, when we had a breakthrough of any kind, we would post it up as well. As soon as we figured out how to dye the Makies different colors we told the community how to do it themselves, if they wanted to”, says Alice.

A collaborative approach to design is part of the Makielab way. She continues:

“It’s the same with the clothes. We design the clothes here, and when we’ve finished, we put them up on the shop, but we also put the patterns up, so if you want to make your own, you can. And if you don’t want to, you can buy them from us.”

Painted and polished Makie. Photo © Copyright My Delicious Bliss.

Moving into the mainstream

Makielab have started a new chapter in their story. They’ve established a foothold with geeks, but they’re looking toward the much larger mainstream toy market. The question is, are the geeks right? Can Alice and her team build Makies into an accessible mass-market product?

Right now, cost is a major obstacle between them and that market. It’s a challenge for any small-scale startup growing a business on bleeding-edge tech:

“We’re a small digital/physical manufacturing startup, operating in an unproven area. Everyone believes in it, and knows it’s going to grow, but there are some really significant questions, like, how long is it going to take for material prices to come down? How long before SLS machines stop costing £125,000 [$186,000], and more like the £1-5k range [$1,500-$7,500]. That changes things radically. The dolls at the moment are quite expensive, compared to Barbie, but that’s a factor of the cost of the powdered plastic. So we need to stay alive during this alpha geek stage, where the technology stops emerging, and becomes mainstream. And I’m hoping that process takes no longer than three or four years!”

The way Makies are marketed also has to change. The language that piques the interest of geeks doesn’t speak to everyone. Until very recently, if you’d visited the Makie.me website, you’d have seen a small but deliberate ‘alpha’ tag up in the corner, along with a to-do list of features still in development, and a badge proudly proclaiming Makies to be the world’s first 3D printed toy. The badge and the to-do list are still there, but the ‘alpha’ tag has gone, the first sign of a shift in language. They’ve just released their first iPad app, Makies Doll Factory, which lets users create digital Makies and then buy the physical doll if they wish. The promotional video is resolutely targeted at a non-technical audience. While it has none of the sickly-sweet coating we’ve come to expect from the traditional toy ad, it’s noticeable (to a geek) that there’s no mention of ‘selective laser sintering’, even just ’3D printing.’ Rather, it’s a ‘giant machine with lasers’ that brings your doll to life.

Makies in their new skin colours: Strawberry Milk, Ice Frosting, Cocoa Bean and Pale Pistachio

They’re working to continually improve the product. Makies are now available in a range of skin colours. And they’re also now toy safety certified; meaning that they can be sold as suitable for kids aged 3 and up. And, though Alice stresses that Makies aren’t just for girls, plans are afoot for a product aimed more at boys.

I think the geeks are right, that what we’re seeing today is just a ‘faint signal’ from the future, when we’ll be sharing the world with many more Makies, and designing, hacking and telling stories with our toys.

Design your own Makie on the Makie.me website, or with the new iPad app.

Andrew Sleigh is a maker, writer and photographer based in Brighton, England. He’s got his eye on a Makie in delicious pale pistachio, and he’d love you to bring your custom Makie to Brighton Mini Maker Faire in September.

AS: How do you scale up the work that’s made by hand?

AT: You don’t really. I mean, you do, with things like laser cutters. One of the great labours of sewing clothes is cutting the cloth, so if you use a cloth that doesn’t fray at the edges … and you have a laser cutter, that problem is solved.

The sewing is manual. But I’m not against the idea of having light casual labour around. As a society, we’ve pushed everyone towards academic qualifications, and now we’ve got a ton of graduates out on the dole, with no jobs for them. And people need flexible work; they always have done…

That said, it’s not our focus. Our focus is on manufacturing toys.

AS: I suppose conceivably, there could be an Etsy after-market in Makie clothes

AT: Exactly, we would love to see that. When you get to the size of Blythe or Barbie, you can build your own secondary market…

One of the central ideas of this piece is that Makies are an unfinished product, and this strikes me as another example of how the community helps grow the value of the product, after it has left the factory gates.