Brendan Dawes: sharing your work

This week, I interviewed the designer and maker Brendan Dawes for my podcast, Looking Sideways. I wrote up some of the interview here.

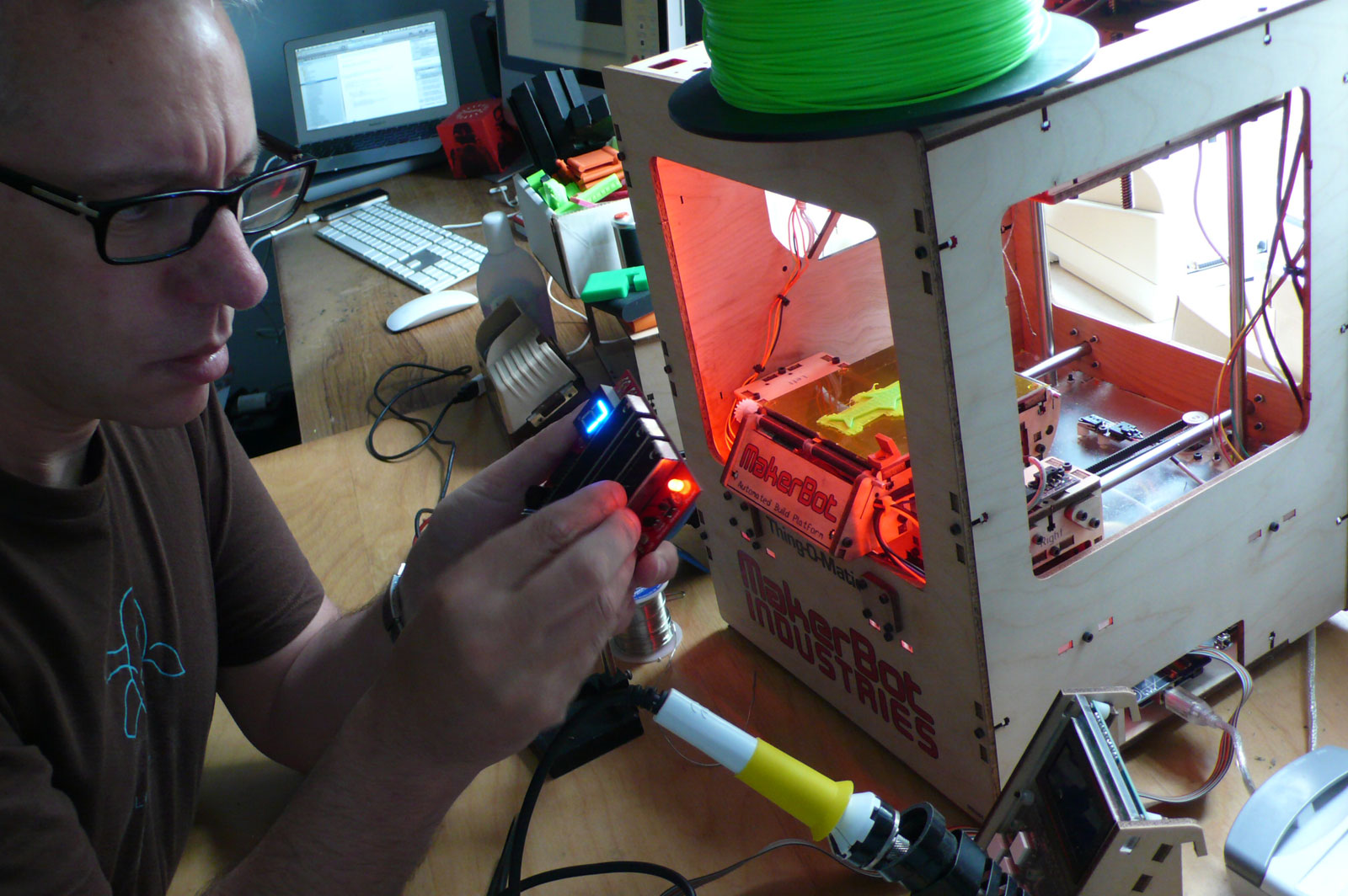

Brendan’s known for early interactive web projects like Psycho Studio, that allows users to remix Hitchcock’s famous shower scene themselves. He’s also known for his physical projects, such as the Moviepeg and Popa phone accessories, and devices that cross the digital/physical divide, such as the Happiness machine, an internet-connected printer that prints random happy thoughts from people across the web.

We talked about designing physical objects that embody hidden digital information:

“I think we should be embracing digital a lot more than we currently do. Digital is hard to touch. It exists in this space that you never actually see. Creating physical things for me has always been about trying to manifest that,” he says.

“One of the projects I’m working on at the moment is a physical box for your Twitter archive. It’s got a little display and a rotary control, and you can quickly scroll backwards and forwards and view past tweets. It’s totally self-contained. You can put it on a shelf and turn it on, and you might look at stuff in the past. Otherwise, what are you going to do with that Twitter archive. You’ve got it, so what? You’re never going to look at it.

“That’s what’s great about physical things. They can be on a shelf, or at home, and they can interrupt your day, and remind you of something just because they’re a physical thing. When they’re on your hard drive, or your phone, or a server somewhere, then you don’t bump into them.”

We also spoke about how makers can get their work out there, even when it may not seem ready for an audience:

“Cinema Redux is a really good example of publishing your stuff even though you might not think it’s perfect. When is it ever perfect?” he says.

“I just published it on my site in 2004. A few blogs picked up on it. John Walters, who’s the editor of Eye magazine, wrote a piece for the Guardian about it.

“Over the years, it got noticed occasionally, and people would link to it. It would be on Digg, and bring my server down. And then in 2007, I got an email from MoMA in New York. They were putting this exhibition together called Design and the Elastic Mind, and they wanted to feature 2 pieces that I’d made. And I was completely blown away. I don’t even have an art qualification. I still remember that email.

“We went to New York, we went to the opening night, there were several thousand people there, and it continues to be ‘a thing’. When people refer to that kind of aesthetic, they call it cinema redux. I did a solo show last year. So it’s been an amazing thing for me, and that’s just come out of playing, and publishing it.”

Brendan makes his living as a maker, spending part of his time working on commissions inspired by more personal experiments he’s shared on the web:

“I’m always surprised at who’s watching this stuff. You just never know. And it wasn’t an instant thing, it took 3 years. My remit to myself is to put stuff out there that gets talked about. It’s not just about getting clients, far from it, but it’s stuff that gets attention, and hopefully attracts the right kind of people to work with.

“The data visualisation thing I did for EE – they had seen some of my other visualisation work, and just approached me to do what turned out to be a really great project. But when I started on that, I didn’t know what I was going to make, and they had to trust me.

“Instagram is interesting. If you’re someone making stuff, trying to get work — the other day, I just posted something on Instagram. Within 5 minutes, someone commissioned that design for a book. Now I haven’t got hundreds of thousands of followers. It was just that this guy who was following me, he runs a festival – he just happened to see it. And it was literally just a photograph of a screen. That was just something I was just playing around with for myself. It shows, you just do not know where this stuff’s going to come from. So push it out there. Use all those channels. They’re all channels for possibilities.”

Listen to the full interview here, or get the podcast in iTunes.